Stephen Polifka Jr. showed up recently at City Hall in New Haven desperate to find work.

"Where should I hang myself?," he said as he sat down to meet with Tirzah Kemp, a city official who helps former prisoners. "I get so frustrated I want to give up."

"I want you to take a deep breath," Kemp said.

Polifka, 46, a carpenter released from prison in 2009, is struggling to find work in a poor economy with a felony criminal record for drug possession. He's staying at a 90-day shelter, surviving on food stamps; he fears returning to drug-ridden streets.

New Haven shares his fears and is among a growing number of cities, states and community groups stepping up efforts to reintegrate newly released prisoners before they commit new crimes. The 2008 federal Second Chance Act has helped fund about 250 prison re-entry programs around the country aimed at reducing recidivism by helping former prisoners.

"Corrections has really come to a crisis," said Leann Duran, director of the New York-based National Re-Entry Resource Center. "We're seeing roughly half the people leaving our prison system and coming back. That's an unacceptably high rate of failure."

The Second Chance Act has provided $198 million nationally so far, officials said. New Haven's program gets about $225,000 a year from a different federal grant, said Amy Meek, who runs the city's program.

While many programs are new and have not been evaluated, research shows the efforts can have promising results, experts say. Studies of re-entry programs in Boston and Baltimore found they were effective in reducing re-arrests, according to Jeremy Travis, president of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

"We can now state, with considerable confidence, that we can intervene in the lives of returning prisoners and reduce their rates of failure, particularly their rates of re-arrest for new crimes," Travis told Congress in 2009.

Participants in the Boston re-entry program had a 30 percent lower rate of recidivism compared to other former prisoners, according to a 2008 evaluation.

In Baltimore, prisoners released between 2001 and 2005, 72 percent of those in the program committed new crimes, compared to nearly 78 percent of other prisoners.

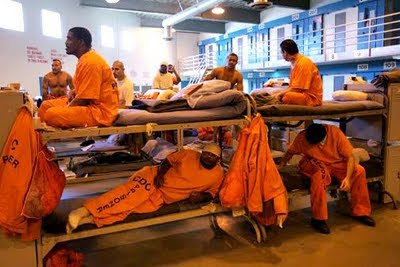

More than 700,000 inmates leave prison annually and many return to hard-hit urban neighborhoods where jobs are scarce and drugs and violence are plentiful. In Connecticut, it costs an average of about $33,000 annually to house a prisoner, according to the Department of Correction.

Nationally, more than 40 percent of ex-cons commit crimes within three years and wind up back behind bars, according to a study by the Pew Center on the States released in April. The study found that 41 states that provided data could save $635 million in one year if they could slash their recidivism rates by 10 percent.

New Haven, home to Yale University, receives 100 to 125 prisoners each month. It has long struggled with crime fueled by repeat offenders who commit an alarming number of shootings and other crimes. About half the people arrested for shootings and homicides in New Haven -- as well as the victims -- have prior felony records, city officials said.

Until a decade ago, little was done to smooth an offender's transition from prison back to the community, experts say. Now cities such as New Haven, where 20 people have been killed so far this year compared to 24 homicides for all of last year, help them with everything from resumes to finding inexpensive clothing.

Kemp and two volunteers recently began visiting a New Haven jail every other week to tell prisoners about agencies that can help them with housing, job skills, and drug treatment. Ten inmates in khaki uniforms sat on bleachers in a stark prison gym last month while the women explained the services, emphasizing the difficult economy.

"This has got to be your hustle," Kemp said, encouraging the prisoners to meet with multiple job agencies and to step up and bolster their resume, self-esteem and get work experience.

State officials say 54 percent of 874 New Haven residents placed on probation in 2009 were rearrested within two years, down slightly from 56 percent of 2,029 residents placed on probation in 2006 and followed for two years. The statewide rate dropped slightly more, from 46 percent to 42 percent over the same period.

Some local activists are skeptical that New Haven's program is making much of a difference.