The theory is simple: Give kids a stable father, and they’ll stay in school and out of jail.

But building fathers isn’t cheap. In North and East Nashville — neighborhoods with the highest rates of single parenting in the city — it’s going to cost $4.8 million over three years.

Federal grant money will help men become better fathers through job training, plus workshops on building relationships, managing anger and going back to school, Metro health officials say. They’ll find the participants through charities and government agencies, men trying to overcome unemployment, conflicts with their children’s mothers or their own lack of parenting as children.

After last week’s grant announcement about the New Life Project, some wondered whether an investment in fatherhood could work. It hasn’t everywhere — a Milwaukee nonprofit has a tough time keeping men in its 13-week Fatherhood Initiative program, its director said, because they lack transportation and don’t understand the benefits.

But local counselors say such education can make a difference. A similar, 11-year-old program in Philadelphia boasts a track record of keeping fathers out of family court and jail.

North Nashville father of four Joshua Talley said he found his own support network to become a better dad but thinks a government program to do the same thing could work. He married at 20 and worked two jobs to support his now ex-wife and infant daughter. Tensions ran high.

He didn’t want to make the same mistake in his second marriage, so he lined up mentors, attended a Metro Health Department boot camp for new dads, earned his GED and began attending Volunteer State Community College’s physical therapy program.

“I’ve learned to show my kids so much more love,” said Talley, whose children are now 14, 11, 6 and 1. “This new program will give men the tools they need to be a better father and will improve our communities. I would have learned so much if I knew of something like this when I was growing up.”

Single-parent rates

City officials targeted North and East Nashville because nearly 60 percent of the households in the neighborhoods are headed by single parents, compared to 39 percent in the rest of the county. Nashville is one of 120 recipients sharing $119 million from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children & Families.

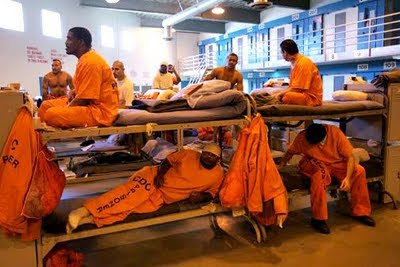

The effort is based on grim statistics that prove the lack of parental involvement can bring drastic consequences, health officials say. Seventy-one percent of all high school dropouts are raised without a father, national data show. About 85 percent of incarcerated youth are reared in a single-parent household.

But experts say children with active fathers and a healthy family life have better educational outcomes, emotional security and fewer behavioral problems. Most fathers want to have a relationship with their children, said Dr. Kimberlee Wyche-Etheridge, director of the Youth and Infants Bureau for Metro Health, and mothers want that, too.

A better road map

David Thomas, a local therapist and director of counseling for men and boys at Daystar Counseling, said educating fathers is key to strengthening families.

“If dads were more informed and had more information, the process of parenting wouldn’t be so overwhelming,” said Thomas, who authored six books on relationships and parenting. He is not involved with the New Life Project.

“A lot of men didn’t have a great road map and were parented by men who were not involved in the day-to-day parenting.”

Several large cities offer programs similar to the one opening here. In Philadelphia, the Fatherhood Initiative Program launched 11 years ago and has served about 5,000 men. A recent analysis shows that of the 276 fathers who were enrolled in 2009, all completed the 12-week program.

“Most men build a better relationship with their children within the first 60 to 90 days,” said Gilbert Coleman, the program’s director. “If we keep our guys out of incarceration from not paying child support, we save the city about $28,000 a man per year.

“Most social services have always been for the mother and the child, but when you look at the statistics, we are leaving the men out of the picture.”

Metro Health is recruiting participants now and will start the program in January.

The Martha O’Bryan Center, the McGruder Family Resource Center, Hadley Park, Matthew Walker Comprehensive Health Center and the PENCIL Foundation will cooperate on grant administration. Many of the classes will be held at Martha O’Bryan and the McGruder Center, while the health center will offer counseling. The participants will also be paired with mentors who can further their parenting skills.

Teen fathers will attend classes at Hadley Park, and the PENCIL Foundation will help identify young fathers to participate.

“We want to help change the stigma and move it away from deadbeat dads to show there are a lot of dedicated fathers out there,” said Robert Taylor, project director for the New Life Project. “This program is for all fathers. The guys like the camaraderie of being around guys that are going through the same things.”

Contact Nancy DeVille at 615-259-8304 or ndeville@tennessean.com or follow on Twitter @devillenews.